Discovering a hard lump or tender knot along your jawline can be both puzzling and concerning. These muscular irregularities in the jaw region are surprisingly common, affecting millions of individuals worldwide who experience varying degrees of discomfort and functional limitations. The complex network of muscles responsible for chewing, speaking, and facial expression can develop these palpable abnormalities for numerous reasons, ranging from simple muscle tension to more complex underlying conditions.

Understanding the potential causes of jaw muscle knots requires examining the intricate anatomy of the masticatory system and the various factors that can disrupt normal muscle function. Whether you’re experiencing a tight band in your masseter muscle or noticing unusual tension in your temporalis region, recognising the underlying mechanisms can help guide appropriate treatment and management strategies.

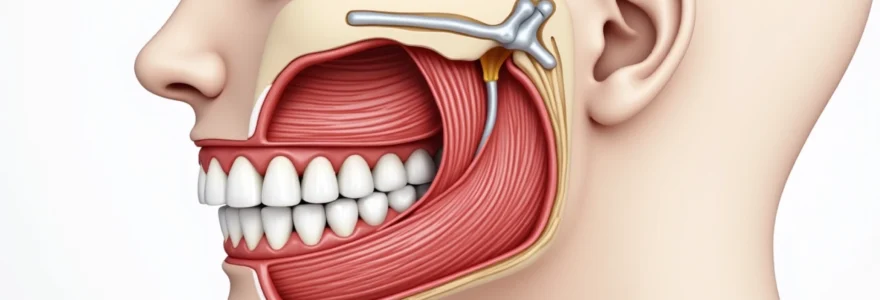

Anatomical structure of the masseter and temporalis muscle complex

The masticatory muscles represent one of the most powerful muscle groups in the human body, capable of generating tremendous force during chewing and jaw closure. These muscles work in precise coordination to facilitate essential functions including mastication, speech articulation, and facial expression. The complexity of this muscular system makes it particularly susceptible to dysfunction and the development of palpable knots or trigger points.

Masseter muscle fascicles and attachment points

The masseter muscle consists of two distinct portions: the superficial and deep layers, each with specific anatomical characteristics and functional roles. The superficial masseter originates from the anterior two-thirds of the zygomatic arch and inserts into the lateral surface of the mandibular ramus and angle. This portion is responsible for the primary jaw-closing action and generates the bulk of chewing force.

The deep masseter fibres originate from the posterior third of the zygomatic arch and the entire medial surface of the arch, inserting into the upper half of the ramus and the coronoid process of the mandible. These deeper fascicles contribute to both jaw closure and slight forward movement of the mandible during grinding motions.

Temporalis muscle fibres and coronoid process connection

The temporalis muscle represents the largest of the masticatory muscles, spanning the temporal fossa and featuring a fan-shaped configuration that allows for complex jaw movements. The muscle fibres converge toward the coronoid process of the mandible, where they insert via a strong tendon. This anatomical arrangement enables the temporalis to perform multiple functions including jaw elevation, retraction, and side-to-side grinding movements.

The anterior fibres of the temporalis run vertically and primarily facilitate jaw closure, whilst the posterior fibres are oriented more horizontally and contribute to jaw retraction. This varied fibre orientation makes the temporalis particularly susceptible to developing trigger points in different regions, each potentially causing distinct pain patterns and functional limitations.

Medial and lateral pterygoid muscle interactions

The pterygoid muscles, though smaller than the masseter and temporalis, play crucial roles in jaw function and can significantly contribute to muscle knot formation. The lateral pterygoid consists of two heads: the superior head originates from the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, whilst the inferior head arises from the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate. Both heads insert into the condylar process of the mandible and the articular disc of the temporomandibular joint.

The medial pterygoid mirrors the masseter muscle’s action but from the internal aspect of the jaw. It originates from the medial surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and inserts into the medial surface of the mandibular ramus. These muscles work synergistically to produce complex jaw movements and can develop tension patterns that manifest as palpable knots or trigger points.

Trigeminal nerve innervation pathways

The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) provides motor innervation to all masticatory muscles through its mandibular division. The masseter and temporalis muscles receive innervation from the masseter and deep temporal nerves respectively, both branches of the anterior division of the mandibular nerve. The pterygoid muscles are innervated by branches from the nerve to the medial pterygoid and the lateral pterygoid nerve.

This complex innervation pattern means that neural dysfunction or irritation can contribute to abnormal muscle tension and trigger point development. Nerve entrapment, inflammation, or central sensitisation can lead to altered muscle firing patterns and the formation of palpable muscle knots throughout the masticatory system.

Myofascial trigger points and muscle knot formation

Myofascial trigger points represent localised areas of muscle hypercontraction that can develop within the masticatory muscles, creating the sensation of knots or tight bands. These trigger points are characterised by their ability to produce both local tenderness and referred pain patterns that can extend well beyond the immediate area of muscle dysfunction. Research indicates that trigger points in jaw muscles are among the most common causes of chronic orofacial pain, affecting up to 85% of individuals with temporomandibular disorders.

Sarcomere contracture mechanisms in jaw muscles

At the cellular level, muscle knots result from sustained sarcomere contracture within localised regions of muscle fibres. In jaw muscles, this process often begins with excessive calcium ion release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to prolonged actin-myosin cross-bridge formation. The high-stress environment of masticatory muscles, which can generate forces exceeding 200 pounds per square inch, makes them particularly susceptible to this type of dysfunction.

The contracture process is self-perpetuating because the shortened sarcomeres compress local blood vessels, reducing oxygen and nutrient delivery whilst simultaneously impairing the removal of metabolic waste products. This creates a cycle of ischaemia and toxin accumulation that maintains the trigger point and contributes to the characteristic tenderness and referred pain patterns associated with jaw muscle knots.

Ischaemic tissue changes and metabolite accumulation

When muscle knots form in the jaw region, the resulting tissue compression creates localised areas of reduced blood flow. This ischaemic environment leads to several biochemical changes that perpetuate the trigger point and contribute to ongoing symptoms. Oxygen depletion triggers anaerobic metabolism, resulting in increased production of lactic acid and other metabolic byproducts that sensitise local pain receptors.

The accumulation of inflammatory mediators, including bradykinin, substance P, and prostaglandins, creates a hypersensitive environment around the trigger point. These substances not only increase pain perception but also contribute to the characteristic referral patterns seen with jaw muscle trigger points, where pressure on a knot in the masseter might produce pain in the ear, teeth, or temple region.

Fascial adhesion development in masticatory muscles

The fascial network surrounding masticatory muscles can develop adhesions and restrictions that contribute to the formation and persistence of muscle knots. These adhesions typically form as a result of chronic muscle tension, inflammation, or previous trauma to the jaw region. The dense fascial connections between the masseter, temporalis, and surrounding structures mean that restrictions in one area can create compensatory tension patterns throughout the entire masticatory system.

Fascial adhesions can alter normal muscle biomechanics, leading to uneven force distribution during jaw movements. This altered mechanical environment predisposes specific muscle regions to overuse and trigger point development, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of dysfunction and pain.

Calcium ion dysregulation and sustained contraction

Calcium ion regulation plays a critical role in normal muscle function, and dysregulation of this system is central to trigger point formation in jaw muscles. Under normal circumstances, calcium ions are released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum to initiate muscle contraction and then actively pumped back into storage to allow relaxation. In trigger points, this regulatory mechanism becomes disrupted, leading to persistently elevated calcium levels and sustained muscle contraction.

The energy-dependent calcium pump systems require adequate ATP production to function properly. When muscle knots develop, the local ischaemia impairs cellular energy production, creating an environment where calcium cannot be effectively sequestered. This results in the characteristic firm, ropey texture of muscle knots and contributes to their resistance to simple stretching or relaxation techniques.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction and associated muscle tension

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction represents one of the primary causes of muscle knot development in the jaw region, affecting approximately 12% of the population at any given time. The intimate relationship between joint mechanics and muscle function means that even subtle alterations in jaw joint alignment or movement can create compensatory muscle tension patterns that manifest as palpable knots or trigger points.

When the temporomandibular joint experiences dysfunction, whether due to disc displacement, arthritic changes, or ligamentous laxity, the surrounding muscles must work harder to maintain jaw stability and function. This increased muscular demand often leads to the development of protective muscle guarding patterns, where certain muscle groups remain in a state of chronic low-level contraction to splint the dysfunctional joint.

The masseter muscle is particularly susceptible to developing knots in response to TMJ dysfunction, as it serves as a primary stabiliser of the mandible during jaw movements. Research demonstrates that individuals with internal derangements of the TMJ show significantly increased masseter muscle activity even during rest periods, suggesting a continuous state of muscle hyperactivity that predisposes to trigger point formation.

Joint dysfunction creates a cascade of muscular adaptations that can persist even after the initial joint problem has resolved. These adaptive patterns often become ingrained in the neuromuscular system, requiring specific therapeutic interventions to break the cycle of dysfunction and restore normal muscle function. The complex feedback loops between joint mechanoreceptors and muscle spindles mean that addressing both joint mechanics and muscle tension is essential for comprehensive treatment of jaw muscle knots.

Disc displacement within the temporomandibular joint creates particularly challenging scenarios for muscle function. When the articular disc becomes displaced, usually in an anterior direction, the normal smooth jaw movements become disrupted, requiring compensatory muscle actions to navigate around the mechanical obstruction. These compensatory patterns typically result in asymmetrical muscle tension, with knots developing more prominently on the affected side.

Bruxism-related masseter muscle hyperactivity

Bruxism, characterised by involuntary grinding or clenching of teeth, represents one of the most significant risk factors for developing muscle knots in the jaw region. This parafunctional activity can occur during sleep (sleep bruxism) or while awake (awake bruxism), with both forms contributing to excessive muscle tension and trigger point development. Studies indicate that individuals with bruxism demonstrate masseter muscle activity levels that are 3-5 times higher than normal during sleep periods.

The repetitive, high-force contractions associated with bruxism create ideal conditions for muscle knot formation through several mechanisms. The sustained muscle tension reduces local blood flow, leading to ischaemic changes within the muscle tissue. Additionally, the eccentric loading patterns during grinding movements can cause microscopic muscle damage, initiating inflammatory responses that contribute to trigger point development.

Sleep bruxism poses particular challenges because the protective reflexes that normally prevent excessive muscle force are diminished during sleep. This allows for the generation of tremendous forces, often exceeding those produced during normal chewing by 10-15 times. The combination of high force and prolonged duration creates a perfect storm for muscle knot development, particularly in the masseter and temporalis muscles.

The cyclical nature of bruxism-related muscle dysfunction creates a self-perpetuating problem where muscle knots and trigger points contribute to altered jaw mechanics, which in turn exacerbate bruxing behaviours.

Stress and anxiety often serve as underlying drivers of bruxism, creating additional layers of complexity in managing jaw muscle knots. The psychological component of bruxism means that effective treatment must address not only the physical muscle dysfunction but also the emotional and behavioural factors that contribute to the parafunctional activity. Cognitive-behavioural interventions, stress management techniques, and relaxation training often form essential components of comprehensive treatment programs.

The relationship between bruxism and muscle knots is bidirectional, with existing trigger points potentially contributing to increased bruxing activity through altered proprioceptive feedback. Muscle knots can change the normal sensory input from jaw muscles, leading to compensatory muscle activation patterns that may perpetuate grinding behaviours. This highlights the importance of addressing muscle dysfunction as part of comprehensive bruxism management.

Inflammatory conditions affecting jaw musculature

Various inflammatory conditions can affect the masticatory muscles, leading to swelling, pain, and the development of palpable abnormalities that may be mistaken for muscle knots. These conditions range from localised inflammatory responses to systemic autoimmune disorders that specifically target muscle tissue. Understanding the inflammatory component of jaw muscle dysfunction is crucial for appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning.

Myositis and autoimmune muscle inflammation

Myositis represents a group of inflammatory muscle diseases that can affect the masticatory muscles, causing swelling, pain, and functional limitations. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are the most common forms that involve jaw muscles, with patients often presenting with difficulty chewing, jaw muscle weakness, and palpable muscle changes that can be mistaken for typical trigger points or muscle knots.

The inflammatory process in myositis involves immune system activation against muscle tissue, leading to cellular infiltration, tissue damage, and subsequent fibrosis. Unlike typical muscle knots caused by mechanical factors, myositis-related muscle changes are characterised by more diffuse involvement and associated systemic symptoms including fatigue, fever, and muscle weakness in other body regions.

Diagnostic differentiation between inflammatory myositis and mechanical muscle knots requires careful clinical evaluation, including blood tests for muscle enzymes (creatine kinase, aldolase) and inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP). Electromyography may reveal characteristic changes in inflammatory muscle disease, whilst muscle biopsy can provide definitive diagnosis in challenging cases.

Bacterial cellulitis in perioral tissues

Bacterial infections affecting the soft tissues around the jaw can create inflammatory changes that extend into the masticatory muscles. Cellulitis in the perioral region typically results from dental infections, facial trauma, or compromised immune function, leading to spreading bacterial inflammation that can involve muscle tissue and create palpable areas of swelling and tenderness.

The most concerning aspect of perioral cellulitis is its potential for rapid progression and involvement of deeper fascial planes. Ludwig’s angina, a specific form of cellulitis affecting the floor of the mouth, can create significant muscle involvement and poses serious risks due to potential airway compromise. Early recognition and aggressive antibiotic treatment are essential for preventing complications.

Distinguishing between infectious and mechanical causes of jaw muscle abnormalities requires careful attention to associated symptoms including fever, regional lymphadenopathy, and the presence of dental pathology. The inflammatory response associated with bacterial infections typically creates more diffuse tissue changes compared to the localised nature of typical muscle knots or trigger points.

Viral infections causing facial muscle swelling

Several viral infections can affect the masticatory muscles either directly or through associated inflammatory responses. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) mononucleosis commonly causes muscle pain and swelling throughout the body, including the jaw muscles. Patients may develop tender, swollen areas in the masseter or temporalis muscles as part of the systemic inflammatory response.

Viral myositis specifically affecting jaw muscles is less common but can occur with influenza, coxsackievirus, and other viral pathogens. The muscle involvement typically presents as diffuse pain and swelling rather than the localised knots associated with mechanical dysfunction. Patients often report concurrent systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, and muscle pain in other body regions.

The resolution of viral-induced muscle changes typically follows the course of the systemic infection, with symptoms gradually improving as immune function recovers. However, some patients may develop persistent muscle dysfunction following viral infections, possibly due to autoimmune mechanisms triggered by the initial viral exposure.

Diagnostic approaches for jaw muscle abnormalities

Accurate diagnosis of jaw muscle knots and abnormalities requires a systematic approach combining clinical examination techniques with appropriate imaging and functional testing methods. The complex anatomy of the masticatory system and the potential for multiple contributing factors necessitate comprehensive evaluation to identify the underlying causes and guide effective treatment strategies.

Palpation techniques for masseter assessment

Systematic palpation of the masseter muscle requires specific techniques to accurately identify areas of dysfunction, trigger points, and abnormal tissue texture. The examination should begin with the patient in a relaxed position, with the jaw slightly open to allow muscle relaxation. Digital palpation using firm but gentle pressure allows identification of taut bands, nodular areas, and regions of increased tenderness.

The examination should include bilateral comparison to identify asymmetries and assess the superficial and deep layers separately. When palpating the superficial masseter, the examiner should work systematically from the zygomatic arch attachment down to the angle of the mandible, noting any areas of increased tension, nodularity, or pain reproduction. The deep masseter requires more focused pressure and can be accessed by having the patient open slightly and probing more posteriorly along the ramus.

Effective trigger point identification involves applying sustained pressure of approximately 4-6 pounds per square inch whilst monitoring for the characteristic “jump sign” or local twitch response. Areas of dysfunction often demonstrate increased tissue density, reduced mobility, and may reproduce the patient’s familiar pain pattern when compressed. The presence of referred pain during palpation provides valuable diagnostic information about the specific trigger point location and its clinical significance.

Ultrasound imaging of masticatory muscles

Ultrasound imaging has emerged as a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluating jaw muscle abnormalities, offering real-time visualisation of muscle structure and function without radiation exposure. High-frequency ultrasound transducers (12-18 MHz) provide excellent resolution for assessing superficial muscle layers and can identify structural changes associated with trigger points, inflammation, and tissue fibrosis. The dynamic nature of ultrasound allows evaluation of muscle contraction patterns and identification of movement abnormalities during jaw function.

Muscle knots and trigger points often appear on ultrasound as hypoechoic (darker) areas within the normal muscle architecture, representing regions of altered tissue density and reduced blood flow. Doppler ultrasound can assess vascular changes within affected muscles, revealing the characteristic reduction in blood flow associated with trigger point formation. This imaging modality also allows measurement of muscle thickness and assessment of fascial plane mobility, providing objective markers of treatment progress.

The non-invasive nature of ultrasound makes it particularly valuable for serial monitoring of treatment response and identifying optimal injection sites for therapeutic interventions. Research demonstrates that ultrasound-guided trigger point injections show superior accuracy and clinical outcomes compared to palpation-guided approaches, highlighting the diagnostic and therapeutic value of this imaging modality.

Electromyography testing for muscle activity analysis

Electromyography (EMG) provides crucial insights into the electrical activity of masticatory muscles and can identify patterns of dysfunction associated with muscle knot formation. Surface EMG electrodes placed over the masseter and temporalis muscles can detect abnormal resting muscle activity, asymmetrical activation patterns, and altered recruitment strategies that contribute to trigger point development. Patients with jaw muscle knots often demonstrate elevated resting EMG activity, indicating chronic low-level muscle contraction.

Needle EMG, whilst more invasive, offers detailed information about motor unit activity and can identify the characteristic electrical silence seen in the contractured regions of trigger points. This technique can also detect spontaneous electrical activity, fibrillation potentials, and other abnormal findings that may indicate inflammatory or neurogenic muscle disease. The combination of surface and needle EMG provides comprehensive assessment of both global muscle function and localised tissue changes.

Functional EMG testing during jaw movements reveals compensatory activation patterns that develop in response to muscle dysfunction. These altered patterns often persist even after trigger points are treated, necessitating specific neuromuscular re-education to restore normal muscle coordination. EMG biofeedback training has proven effective in helping patients recognise and modify abnormal muscle activation patterns contributing to jaw dysfunction.

MRI evaluation of soft tissue changes

Magnetic resonance imaging offers superior soft tissue contrast and can provide detailed visualisation of muscle architecture, fascial planes, and inflammatory changes within the masticatory muscles. T2-weighted sequences are particularly valuable for identifying areas of muscle oedema, fibrosis, and inflammatory infiltration that may contribute to muscle knot formation. The ability to visualise muscles in multiple planes allows comprehensive assessment of the three-dimensional relationship between different muscle groups.

Trigger points and muscle knots may appear as areas of altered signal intensity on MRI, though the findings are often subtle and require experienced interpretation. More obvious changes include muscle atrophy, fatty infiltration, and fascial thickening that can develop in chronic cases of muscle dysfunction. Dynamic MRI sequences can assess muscle function during jaw movements, revealing patterns of abnormal activation or coordination deficits.

The high cost and limited availability of MRI typically reserve this modality for complex cases where other diagnostic methods have been inconclusive or when inflammatory muscle disease is suspected. However, the detailed anatomical information provided by MRI can be invaluable for surgical planning and understanding the full extent of muscle involvement in complicated cases of jaw dysfunction.

Advanced imaging techniques continue to evolve our understanding of muscle knot pathophysiology, with new MRI sequences and analysis methods providing unprecedented insights into the structural and functional changes associated with trigger point formation.

The integration of multiple diagnostic approaches creates a comprehensive picture of jaw muscle dysfunction, enabling clinicians to develop targeted treatment strategies that address both the symptoms and underlying causes of muscle knots. This multimodal assessment approach has revolutionised the management of complex jaw muscle disorders, leading to improved treatment outcomes and reduced chronicity of symptoms. Understanding the specific diagnostic findings associated with different causes of jaw muscle knots allows for more precise therapeutic interventions and better patient education about their condition.