The cervical spine’s natural curvature plays a fundamental role in maintaining optimal spinal biomechanics and overall neurological health. When this essential lordotic curve becomes compromised or lost entirely, the implications extend far beyond simple postural concerns. Loss of cervical lordosis represents a significant structural alteration that can trigger a cascade of musculoskeletal and neurological complications, affecting everything from basic head movement to complex neural pathways.

Modern lifestyle factors, combined with an increasing understanding of spinal biomechanics, have brought cervical straightening into sharp clinical focus. The condition affects millions globally , yet many healthcare professionals still underestimate its profound impact on patient wellbeing. Understanding the intricate relationship between cervical curvature and systemic health becomes crucial for both prevention and effective treatment strategies.

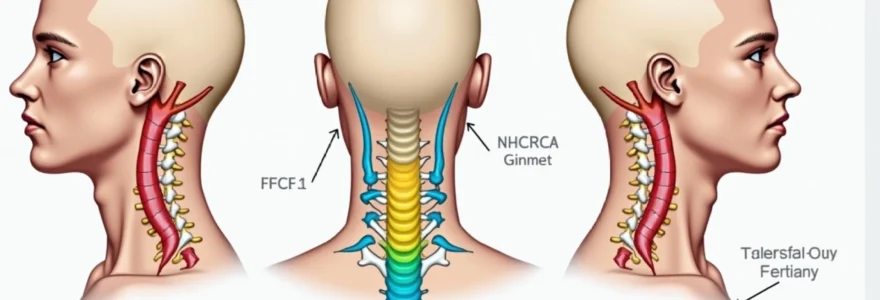

Anatomical structure and biomechanics of normal cervical lordosis

The cervical spine’s architectural design represents one of nature’s most sophisticated engineering marvels, combining remarkable mobility with essential stability. This delicate balance relies heavily on the maintenance of proper lordotic curvature, which serves as the foundation for optimal cervical function. The normal cervical lordosis ranges between 20 to 40 degrees when measured using standardised radiographic techniques, though individual variations exist based on age, gender, and constitutional factors.

Understanding the biomechanical principles underlying cervical lordosis reveals why its preservation is so critical. The lordotic curve functions as a natural shock absorber, distributing mechanical forces evenly throughout the cervical vertebrae during daily activities. When you consider that the average human head weighs approximately 10-12 pounds, the importance of this curved structure becomes immediately apparent. Without proper lordosis, the cervical spine must work exponentially harder to support this weight, leading to accelerated degenerative changes and muscular fatigue.

C1-C7 vertebral alignment and physiological curvature parameters

The seven cervical vertebrae form a complex kinetic chain, each contributing uniquely to overall cervical lordosis. The upper cervical segments (C1-C2) primarily facilitate rotational movement, whilst the lower segments (C3-C7) contribute more significantly to the lordotic curve’s formation. Research indicates that the C4-C6 region typically demonstrates the most pronounced lordotic angulation, with C5 often representing the apex of the cervical curve.

Vertebral alignment parameters reveal fascinating insights into cervical biomechanics. The physiological cervical lordosis demonstrates a progressive increase in vertebral body height from superior to inferior levels, with the C7 vertebral body being substantially larger than C3. This graduated size difference contributes to the natural wedging effect that helps maintain the lordotic curve. Disruption of these alignment parameters can fundamentally alter cervical biomechanics, leading to compensatory changes throughout the entire spinal column.

Atlas-axis complex function in maintaining cervical lordotic curve

The atlas-axis complex (C1-C2) represents perhaps the most specialised joint system in the human body, contributing approximately 50% of total cervical rotation whilst maintaining crucial relationships with the occipital bone above. The atlas lacks a traditional vertebral body, instead forming a ring-like structure that articulates with the occipital condyles. This unique anatomy allows for the nodding motion of the head whilst providing a stable platform for the axis below.

The axis, or C2 vertebra, features the distinctive odontoid process (dens) that projects upward through the atlas ring, creating a pivot point for rotational movement. This arrangement significantly influences the overall cervical lordotic curve by establishing the foundational angle from which the lower cervical segments must adapt. Any disruption to atlas-axis alignment can create a ripple effect throughout the entire cervical spine, potentially contributing to lordotic loss and associated symptoms.

Intervertebral disc height distribution throughout cervical spine

Cervical intervertebral discs demonstrate a unique height distribution pattern that directly influences lordotic curvature maintenance. The discs progressively increase in height from C2-C3 to C6-C7, with the C5-C6 and C6-C7 discs being the tallest. This graduated height difference contributes significantly to the natural lordotic wedging effect, with healthy discs maintaining approximately 40% of total cervical lordosis.

The relationship between disc height and lordotic curvature becomes particularly evident in degenerative conditions. As cervical discs lose height through degeneration, the natural wedging effect diminishes, contributing to progressive lordotic straightening. Studies demonstrate that even modest disc height loss can reduce cervical lordosis by 2-4 degrees per affected level, highlighting the critical importance of disc health in maintaining proper cervical curvature.

Ligamentous support systems: anterior longitudinal and posterior longitudinal ligaments

The cervical spine’s ligamentous support systems play crucial roles in maintaining lordotic curvature whilst allowing necessary mobility. The anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) runs along the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies and discs, providing restraint against excessive extension whilst supporting the natural lordotic curve. This ligament demonstrates varying thickness throughout the cervical spine, being thickest at the mid-cervical levels where lordotic forces are greatest.

The posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) provides complementary support along the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies within the spinal canal. Unlike its anterior counterpart, the PLL narrows as it descends, becoming relatively thin at the lower cervical levels. This anatomical variation has significant clinical implications, as lower cervical disc herniations often occur posterolaterally where PLL support is minimal. Ligamentous integrity directly influences the spine’s ability to maintain proper curvature under varying load conditions.

Radiological assessment methods for cervical lordosis measurement

Accurate assessment of cervical lordosis requires sophisticated radiological techniques that can quantify both the degree of curvature loss and its clinical significance. Modern imaging protocols have evolved considerably, incorporating advanced measurement methodologies that provide unprecedented insight into cervical biomechanics. The choice of assessment method significantly impacts diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning, making standardised approaches essential for optimal patient outcomes.

Contemporary cervical spine imaging extends beyond simple lateral radiographs to include dynamic studies, three-dimensional reconstructions, and advanced soft tissue evaluation techniques. Each imaging modality offers unique advantages in assessing different aspects of cervical lordosis, from bony alignment to soft tissue integrity. Understanding the strengths and limitations of various assessment methods enables healthcare providers to select the most appropriate imaging strategy for individual patients.

Cobb angle technique for quantifying cervical curvature loss

The Cobb angle measurement technique represents the gold standard for quantifying cervical lordosis in clinical practice. This method involves drawing lines parallel to the superior endplate of C2 and the inferior endplate of C7, then measuring the angle between perpendicular lines drawn from these references. Normal cervical lordosis typically measures between 20-40 degrees using this technique, though significant individual variation exists based on age, gender, and constitutional factors.

Modified Cobb angle techniques have been developed to address specific clinical scenarios, including the posterior tangent method that utilises the posterior vertebral body margins instead of endplates. Research demonstrates excellent inter-observer reliability for Cobb angle measurements when standardised techniques are employed, with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.90 in most studies. Accuracy of Cobb angle measurement depends heavily on proper patient positioning and radiographic technique, emphasising the importance of standardised imaging protocols.

Harrison posterior tangent method and reference values

The Harrison Posterior Tangent Method (PTM) offers an alternative approach to cervical lordosis measurement that some researchers argue provides superior accuracy compared to traditional Cobb techniques. This method involves drawing lines tangent to the posterior margins of the C2 and C7 vertebral bodies, measuring the angle between these tangent lines. Normal values using PTM typically range from -25.8° to -1.4°, with negative values indicating lordotic curvature.

Reference values for the Harrison PTM have been established through extensive normative studies involving thousands of asymptomatic subjects. These studies reveal age-related changes in cervical lordosis, with younger individuals typically demonstrating greater lordotic curvature that gradually decreases with advancing age. Gender differences also emerge, with females generally showing slightly less cervical lordosis than males. Understanding these normative variations becomes crucial when interpreting individual patient measurements and planning appropriate interventions.

Sagittal vertical axis deviation in lateral cervical radiographs

Sagittal vertical axis (SVA) measurement provides valuable insight into global cervical alignment and its relationship to overall spinal balance. The cervical SVA is measured as the horizontal distance between a vertical line dropped from the center of C7 and a vertical line drawn from the posterior-superior corner of C2. Normal cervical SVA typically measures less than 40mm, with greater values indicating progressive forward head posture and cervical malalignment.

The relationship between cervical SVA and lordotic curvature demonstrates strong clinical correlation, with loss of lordosis consistently associated with increased SVA measurements. This relationship becomes particularly important when assessing treatment outcomes, as restoration of cervical lordosis typically correlates with improvement in SVA measurements. Research indicates that every 10-degree improvement in cervical lordosis corresponds to approximately 15-20mm improvement in cervical SVA, highlighting the biomechanical interconnection between these parameters.

MRI T2-Weighted imaging for soft tissue evaluation

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with T2-weighted sequences provides unparalleled soft tissue detail essential for comprehensive cervical spine assessment. T2-weighted imaging excels at evaluating disc hydration, neural compression, and ligamentous integrity—factors that significantly influence cervical lordosis maintenance. The ability to visualise soft tissue structures in multiple planes allows for detailed assessment of how lordotic loss affects surrounding anatomical structures.

Advanced MRI techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging and dynamic studies, are expanding our understanding of how cervical straightening affects neural function and cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. These sophisticated imaging methods reveal that loss of cervical lordosis can significantly alter neural pathway integrity and fluid flow patterns within the cervical spinal canal. MRI findings often correlate strongly with clinical symptoms, particularly in cases involving neural compression or myelopathic changes secondary to cervical straightening.

Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of cervical lordosis loss

The pathophysiological consequences of cervical lordosis loss extend far beyond simple postural changes, creating a complex cascade of biomechanical and neurological alterations that can significantly impact patient quality of life. When the natural cervical curve straightens or reverses, the entire kinetic chain from the occiput to the thoracic spine must adapt, often resulting in compensatory mechanisms that generate their own set of problems. Understanding these pathophysiological changes is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies and predicting long-term outcomes.

The biomechanical implications of cervical straightening create a domino effect throughout the musculoskeletal system. As the head translates forward relative to the cervical spine, the centre of gravity shifts anteriorly, requiring increased muscular effort to maintain upright posture. This altered biomechanical environment places excessive strain on posterior cervical muscles, ligaments, and joint structures, leading to accelerated degenerative changes and chronic pain patterns. The condition affects approximately 60% of adults over age 40, with prevalence increasing significantly in occupations requiring prolonged forward head positioning.

Forward head posture syndrome and suboccipital muscle tension

Forward head posture syndrome represents one of the most common and clinically significant manifestations of cervical lordosis loss. This condition involves anterior translation of the head relative to the cervical spine, effectively doubling or tripling the effective weight that cervical structures must support. Research demonstrates that for every inch of forward head translation, the effective weight of the head increases by approximately 10 pounds, placing enormous strain on posterior cervical muscles.

Suboccipital muscle tension develops as these small, deep muscles work overtime to maintain visual horizontal despite the altered cervical alignment. The suboccipital muscles, including the rectus capitis posterior major and minor, and the obliquus capitis superior and inferior, become chronically contracted in an attempt to prevent excessive cervical flexion. This chronic contraction pattern creates trigger points, restricts normal cervical motion, and can contribute to tension-type headaches affecting up to 38% of patients with significant cervical straightening.

The suboccipital region contains the highest concentration of muscle spindles in the human body, making it exquisitely sensitive to postural changes and positioning alterations associated with cervical lordosis loss.

Cervical radiculopathy from neural foraminal stenosis

Loss of cervical lordosis significantly alters the dimensions and geometry of neural foramina, often leading to nerve root compression and radicular symptoms. The neural foramina normally demonstrate a kidney-bean shape in cross-section, providing adequate space for nerve root passage along with accompanying blood vessels. However, as cervical straightening progresses, these foraminal spaces become narrowed both anteroposteriorly and in height, creating potential compression sites.

Clinical manifestations of cervical radiculopathy secondary to foraminal stenosis include arm pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in specific dermatomal and myotomal distributions. The C6 and C7 nerve roots are most commonly affected, corresponding to the levels where lordotic loss is typically most pronounced. Approximately 25% of patients with significant cervical straightening develop some degree of radicular symptoms, with conservative treatment proving effective in roughly 70% of cases when implemented early in the disease process.

Vertebral artery compromise and vertebrobasilar insufficiency

The vertebral arteries traverse the cervical spine through the transverse foramina of C6 through C1, making them susceptible to compression or distortion when normal cervical alignment is lost. Cervical straightening can alter the natural course of these vital vessels, potentially leading to reduced blood flow to the posterior circulation of the brain. This vascular compromise becomes particularly problematic during cervical rotation or extension movements.

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency symptoms associated with cervical lordosis loss include dizziness, vertigo, visual disturbances, and in severe cases, drop attacks. These symptoms often worsen with specific head positions or movements, creating a functional disability that extends beyond simple neck pain. Studies indicate that up to 15% of patients with severe cervical straightening experience some degree of vertebrobasilar symptoms, though the exact mechanisms remain subject to ongoing research and debate within the medical community.

Cervical myelopathy development in severe straightening cases

Severe cervical straightening can progress to cervical myelopathy when spinal cord compression occurs within the cervical canal. The normal cervical lordosis helps maintain optimal spinal cord positioning within the canal, preventing contact with surrounding bony and ligamentous structures. When this curvature is lost, the spinal cord may experience direct compression, particularly during extension movements that further narrow the canal diameter.

Myelopathic symptoms include gait instability, upper extremity clumsiness, loss of fine motor control, and in advanced cases, bowel and bladder dysfunction. The development of myelopathy represents a surgical emergency requiring prompt intervention to prevent permanent neurological damage. Early recognition of myelopathic signs becomes crucial, as studies demonstrate significantly better outcomes when surgical decompression is performed before severe neurological deficits develop. The Nurick grading scale helps classify myelopathy severity and guides treatment decisions.

Occipital neuralgia and greater occipital nerve irritation

The greater occipital nerve, arising from the C2 nerve root, becomes particularly vulnerable to irritation when cervical lordosis is lost. This nerve pierces through the tendinous insertions of the trapezius and semispinalis capitis muscles before innervating the posterior scalp. Altered biomechanics associated with cervical straightening can create tension and compression points along this nerve pathway, leading to the characteristic symptoms of occipital neuralgia.

Patients with occipital neuralgia typically describe sharp, electric shock-like pain radiating from the suboccipital region to the vertex of the skull, often following the distribution of the greater occipital nerve. The pain may be triggered by light touch, hair brushing, or specific head movements. Treatment often involves a combination of postural correction, targeted muscle releases, and in refractory cases, greater occipital nerve blocks. Response to diagnostic nerve blocks confirms the diagnosis and helps guide long-term treatment strategies.

Aetiological factors contributing to cervical straight

ening

The aetiological landscape of cervical lordosis loss encompasses a complex interplay of occupational, lifestyle, pathological, and developmental factors that contribute to progressive cervical straightening. Understanding these contributing factors is essential for both prevention and targeted treatment strategies. Modern society has introduced unprecedented challenges to cervical spine health, with technological advancement creating new patterns of cervical stress and strain that were virtually unknown just decades ago.

Occupational hazards represent perhaps the most significant modifiable risk factor for cervical lordosis loss. Professions requiring sustained forward head posturing—including computer workers, surgeons, dentists, and assembly line workers—demonstrate significantly higher rates of cervical straightening compared to the general population. Studies indicate that individuals spending more than 6 hours daily in forward head postures show measurable lordotic loss within just 12 months of exposure, highlighting the rapid progression possible under sustained biomechanical stress.

Age-related degenerative changes contribute substantially to cervical lordosis loss through multiple mechanisms. Intervertebral disc dehydration and height loss reduce the natural wedging effect that maintains cervical curvature, whilst facet joint arthropathy alters normal movement patterns and joint mechanics. Ligamentous laxity associated with ageing compromises the spine’s ability to maintain proper alignment under load, leading to progressive postural deterioration. Research demonstrates that cervical lordosis decreases by approximately 1-2 degrees per decade after age 40, with accelerated loss occurring in individuals with pre-existing postural abnormalities.

Traumatic injuries, particularly whiplash-associated disorders from motor vehicle accidents, can acutely disrupt cervical alignment and initiate progressive lordotic loss. The hyperextension-hyperflexion mechanism damages anterior cervical structures including the anterior longitudinal ligament and intervertebral discs, whilst posterior structures including facet joint capsules and interspinous ligaments may be stretched or torn. Post-traumatic cervical straightening occurs in approximately 40% of significant whiplash cases, often developing gradually over months to years following the initial injury as damaged structures fail to maintain normal alignment.

Diagnostic imaging protocols and differential diagnosis considerations

Comprehensive diagnostic evaluation of cervical lordosis loss requires systematic imaging protocols that assess both static alignment and dynamic function. The diagnostic process must differentiate between primary cervical straightening and secondary changes resulting from adjacent segment pathology or systemic conditions. Modern imaging techniques provide unprecedented detail regarding cervical spine structure and function, enabling precise diagnosis and treatment planning.

Standard imaging protocols begin with standing lateral cervical radiographs obtained in the neutral position with standardised patient positioning. The patient should maintain a natural head position while looking straight ahead at eye level, with arms relaxed at the sides to prevent shoulder elevation that might artificially alter cervical alignment. Proper radiographic technique is crucial for accurate measurement, as slight variations in patient positioning or X-ray beam angulation can significantly affect lordosis measurements and lead to diagnostic errors.

Dynamic imaging studies, including flexion and extension lateral radiographs, provide valuable information about segmental motion and instability patterns that may contribute to lordotic loss. These studies reveal hypermobility or hypomobility at specific cervical levels, helping identify segments requiring targeted intervention. Functional radiographs also demonstrate compensatory mechanisms, such as increased upper cervical extension in patients with lower cervical straightening, which influences treatment planning and expected outcomes.

Advanced cross-sectional imaging using MRI becomes essential when neurological symptoms accompany cervical straightening. T2-weighted sagittal images excel at demonstrating disc degeneration, ligamentous injury, and neural compression that may result from or contribute to lordotic loss. T1-weighted images provide excellent anatomical detail of vertebral body alignment and bone marrow signal changes that might indicate underlying pathology. Gradient echo sequences can reveal subtle spinal cord signal changes suggestive of myelomalacia in cases where cervical straightening has progressed to spinal cord compression.

Differential diagnosis considerations must include conditions that can mimic or contribute to cervical lordosis loss. Ankylosing spondylitis produces characteristic bamboo spine appearance with progressive fusion and straightening of the cervical spine, typically accompanied by inflammatory markers and specific genetic patterns. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) creates flowing calcification along the anterior longitudinal ligament, potentially restricting cervical extension and contributing to apparent lordotic loss. Rheumatoid arthritis can cause atlantoaxial instability and cervical straightening through inflammatory destruction of ligamentous structures, particularly at the upper cervical levels.

Conservative treatment approaches and rehabilitation strategies

Conservative management of cervical lordosis loss requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses the underlying biomechanical dysfunction whilst managing symptoms and preventing progression. Successful treatment protocols combine postural correction, targeted strengthening exercises, manual therapy techniques, and ergonomic modifications to restore optimal cervical alignment and function. The evidence strongly supports conservative management as the first-line treatment for most patients with cervical straightening, with surgical intervention reserved for cases involving progressive neurological compromise.

Postural rehabilitation forms the cornerstone of conservative treatment, focusing on restoration of normal cervical curvature through specific exercise protocols and movement re-education. The McKenzie method employs repeated cervical extension exercises to restore lordotic curvature, with studies demonstrating significant improvement in both radiographic alignment and clinical symptoms in approximately 75% of patients when properly applied. Cervical retraction exercises specifically target the deep neck flexors whilst stretching anterior cervical structures that may have adaptively shortened, creating a balanced approach to postural correction.

Strengthening protocols must address both the deep cervical stabilisers and the larger superficial muscles that support cervical alignment. The deep neck flexors, including the longus capitis and longus colli muscles, play crucial roles in maintaining cervical lordosis and require specific activation techniques due to their tendency to become inhibited in patients with cervical dysfunction. Craniocervical flexion exercises using pressure biofeedback units help patients learn to activate these muscles selectively without overcompensation from superficial flexors like the sternocleidomastoid.

Manual therapy techniques, including spinal manipulation and mobilisation, can help restore segmental motion and reduce muscle tension associated with cervical straightening. High-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation of restricted cervical segments may improve joint mobility and reduce pain, though careful patient selection is essential to avoid complications. Soft tissue techniques including trigger point therapy, myofascial release, and deep tissue massage address the muscular imbalances and tension patterns that both contribute to and result from cervical lordosis loss.

Ergonomic modifications represent a crucial component of long-term management, particularly for patients whose occupational demands contributed to their cervical straightening. Computer workstation adjustments should position the monitor at eye level to reduce forward head posturing, whilst ergonomic keyboards and mouse positioning can minimise upper extremity tension that may affect cervical alignment. Regular breaks from sustained postures every 30-45 minutes allow tissues to recover and prevent the development of adaptive shortening in anterior cervical structures.

Patient education plays a vital role in successful conservative management, as individuals must understand the relationship between their daily activities and cervical health. Teaching patients to recognise early warning signs of postural fatigue and providing strategies for self-correction empowers them to take an active role in their recovery. Home exercise programs must be individualised based on specific deficits identified during clinical examination, with progression guidelines that prevent overexertion whilst promoting gradual improvement in cervical function.

Adjunctive therapies may enhance the effectiveness of primary conservative treatments in selected patients. Cervical traction, either manual or mechanical, can help decompress neural structures and provide temporary relief of radicular symptoms while other treatments address underlying postural dysfunction. Heat therapy before exercise sessions helps prepare tissues for stretching and mobilisation, whilst cold therapy after treatment sessions can reduce inflammation and muscle soreness that might otherwise limit patient compliance with exercise protocols.